E a polêmica continua...

Sei lá, se ver o post do realclimate, acho que não há muita "polêmica", não mais do que no sentido que há "polêmica" na teoria do Design Inteligente ou na teoria da afro-burrice Watsoniana.

O principal trecho:

They call it "Internal Radiative Forcing." We call it "weather."

In Spencer and Braswell (2008), and to an even greater extent in his blog article, Spencer tries to introduce the rather peculiar notion of "internal radiative forcing" as distinct from cloud or water vapor feedback. He goes so far as to say that the IPCC is biased against "internal radiative forcing," in favor of treating cloud effects as feedback. Just what does he mean by this notion? And what, if any, difference does it make to the way IPCC models are formulated? The answer to the latter question is easy: none, since the concept of feedbacks is just something used to try to make sense of what a model does, and does not actually enter into the formulation of the model itself.

Clouds respond on a time scale of hours to weather conditions like the appearance of fronts, to oceanic conditions, and to external radiative forcing (such as the rising and setting of the Sun). Does Spencer really think that a subsystem with such a quick intrinsic time scale can just up and decide to lock into some new configuration and stay there for decades, forcing the ocean to be dragged along into some compatible state? Or does he perhaps mean that slow components,like the ocean, modulate the clouds, and the resulting cloud radiative forcing amplifies or damps the resulting interannual or decadal variability? That latter sounds a lot like a cloud feedback to me — acting on natural variability whose root cause is in the ponderous motions of the ocean.

Think of it like a pot of water boiling on a stove. What ultimately controls the rate of boiling, the setting of the stove knob or the turbulent fluctuations of the bubbles rising through the water? Roy's idea about clouds is like saying that you should expect big, long-lasting variations in the boiling rate because sometimes all the steam bubbles will decide to form on the left half of the pot leaving the right half bubble-free — and that things will remain that way despite all the turbulence for hours on end.

The only sense that can be made of Spencer's notion is that there is some natural variability in the climate system, which in turn causes a natural variability to some extent in the radiation budget of the planet, which in turn may modify the natural variability. Is this news? Is this shocking? Is this something that should lead us to doubt model predictions of global warming? No — it is just part and parcel of the same old question of whether the pattern of the 20th and 21st century can be ascribed to natural variability without the effect of anthropogenic greenhouse gases. The IPCC, among others, nailed that, and nobody has demonstrated that natural variability can do the trick. Roy thinks he has, but as we shall soon see, it's all a matter of how you run your ingredients through the food processor.Na parte seguinte ele tenta reproduzir os gráficos do Roy Spencer, e explica que tipo de dados seriam necessários para isso:

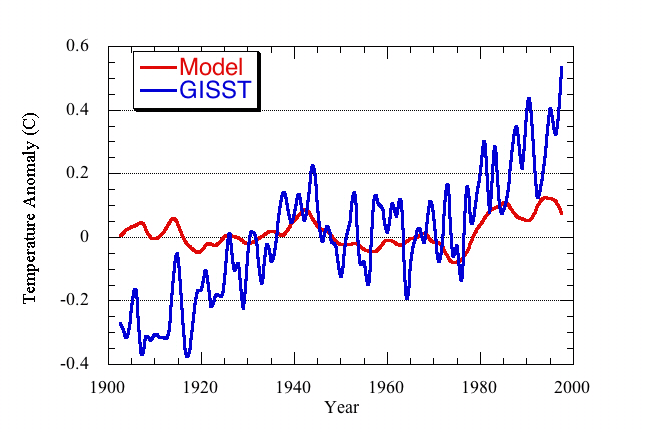

Roy is really taken with this graph. So much so that he uses it as a banner near the top of his climate confusion web site under the heading "Could Global Warming Be Mostly Natural?" But is it as good as it looks? To find out, I programmed up his model myself, but chose the set of adjustable parameters based on compatibility with observations constraining reasonable magnitudes for these parameters. Here's what I came up with:

Roy is really taken with this graph. So much so that he uses it as a banner near the top of his climate confusion web site under the heading "Could Global Warming Be Mostly Natural?" But is it as good as it looks? To find out, I programmed up his model myself, but chose the set of adjustable parameters based on compatibility with observations constraining reasonable magnitudes for these parameters. Here's what I came up with:

So why does Roy's graph look so much better than mine? As Julia Child said, "It's so beautifully arranged on the plate - you know someone's fingers have been all over it."

A Cooking lesson

Lesson One: Jack up the radiative forcing beyond all reason. [...]Minha posição quanto a isso é a seguinte:

Não importa se somos responsáveis por deixar as coisas como estão agora. Mesmo que a gente contribua com 0,1% das mudanças que estamos observando, não é melhor começarmos a contribuir apenas com 0,05% disso?

Além disso, não precisa olhar para o planeta para vermos que tem algo errado com nossa política energética. Basta olhar pro horizonte paulistano no mês de julho.

Eu acho que seria melhor, mas talvez fosse um luxo. A última estratégia dos ex-negacionistas agora é uma argumentação que até tem algum sentido, ainda que dependa em algo de uma certa fé cornucopiana.

Dizem basicamente que as políticas para redução de emissão de CO2 são muitas vezes, quase sempre, mais caras, e logo entraves para o desenvolvimento. Ao mesmo tempo, o aquecimento não vai parar em curto prazo, há uma certa "inércia" (isso não é algo contestado, tanto quanto me lembro) e então as políticas de contorno e remediação tem que ser levadas em conta, e quanto mais se economizar em práticas preventivas de longo prazo, cujo efeito positivo não será visto talvez por ninguém vivo ou quase ninguém, melhor se poderá remediar a situação em curto prazo, melhorando as condições de vida para as pessoas vivas e as próximas a nascerem.

Se o aquecimento tivesse uma parcela da causa humana significativamente menor do que tem, esse raciocínio seria ainda mais imperativo.

Uma exposição mais detalhada da argumentação:

Cato Institute Event Podcast - What to Do about Climate ChangeAlerto que deve estar preparado para umas falácias salpicadas bem difíceis de engolir. Na página tem do lado direito (no Opera ao menos) uma caixa de navegação com transcrições parciais trechos específicos.